BookWorthy Chats with John Hendrix

- Valerie

- Sep 4, 2024

- 20 min read

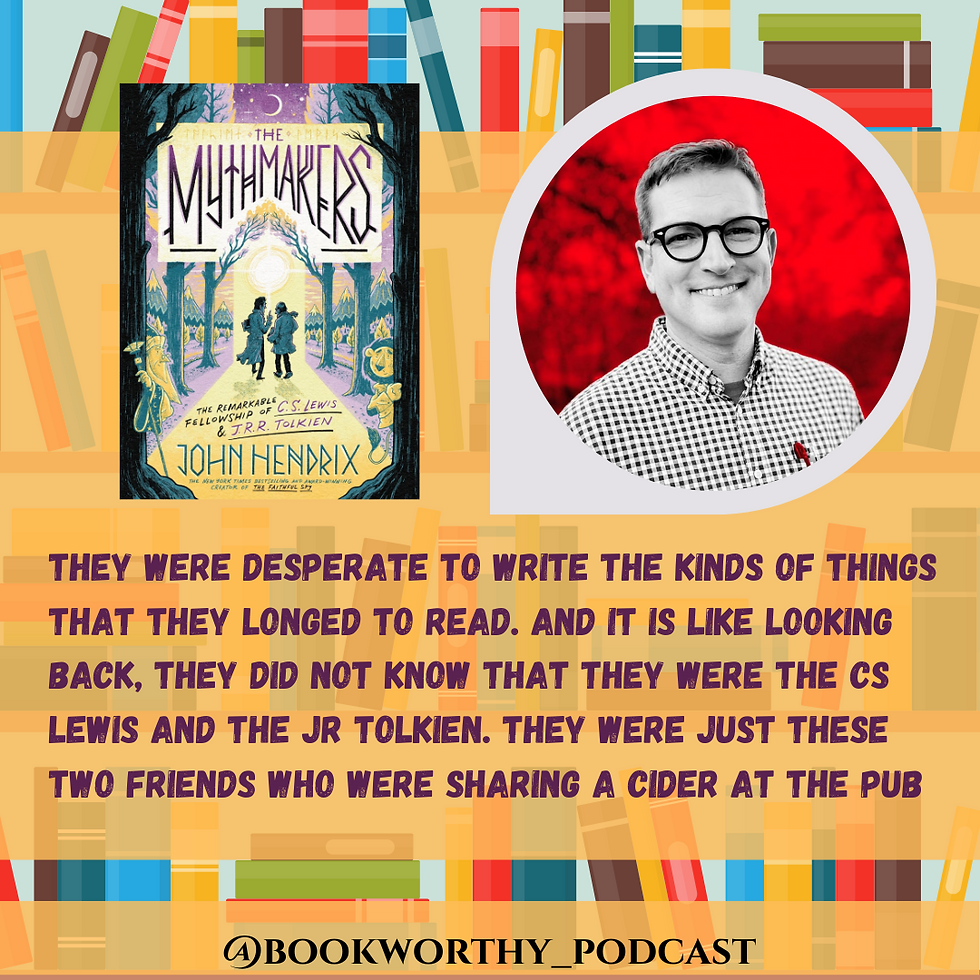

Valerie - Welcome to Bookworthy. Today we're talking with New York Times bestselling illustrator and author of many children's books, John Hendrix. His latest book is coming out here in September, The Mythmakers, the remarkable fellowship of C .S. Lewis and J . R .R. Tolkien. In this graphic novel, John reveals the shared story of friendship and all of its ups and downs that gave Lewis and Tolkien the confidence to re-enchant the 20th century and alter the course of storytelling and literature. Welcome to Bookworthy, John.

John -Thanks, so glad to be here.

Valerie -I'm glad to have you. I had to force my 15-year-old to go to school today because he wanted to participate in this interview. We are big fans of your books and your art in our house. And so it's a joy to have you here. But I'm sorry to say we have to start with the hardest question. If you could only choose one, which would it be The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe or The Hobbit?

John -Oh, man. I mean, the one in The Hobbit would probably be my choice. It's very difficult only because it was my the Hobbit was my entry point to fantasy as just a genre. And it truly happened with like the book cover on my copy of The Hobbit I had as a kid. And it just had this amazing drawing of Smaug on it. And it just It was like, I don't know what this is, but I need to read it. So, I mean, that's a very close race, but probably the hump. Yeah.

Valerie -I know it was a hard question, I know. But did you ever watch the 1980 version of The Hobbit and see Smog in that? Yes, we recently watched The Hobbit with the most recent version of The Hobbit with our boys and that has been fun to watch them be just odd and I don't know, just introduce these characters that we've loved, me and my husband and it's been a joy to share that with them.

John - Yeah, I think it's an underrated version in a lot of ways. It holds up. I mean, I think if you look aside from some of the stylistic things that maybe feel dated, I think it's a good adaptation.

Valerie -Most definitely. And I, what is it? I can't remember the particular film group that did that. They did a lot of movies in the eighties. Yes, Rankin and Bass. And, I loved all of the work that they did in The Last Unicorn. Uh, what, trying to think of the others, but Flight of Dragons, you know, just these great classic stories.

John- Yeah, Rankin and Bass. There was a Lord of the Rings animated film that was like rotoscoped and that one does not hold up. That's not great. The best thing that came out of that one was the poster. But yeah.

Valerie -Well, John, you have combined some of my favorite things in this book, which are the life and the work of both CS Lewis and Token, as well as history and art that engages my kids. Tell us a little bit about the inspiration behind your book, The Mythmakers.

John -Well, of course, I grew up reading these two these two Tweety professors. Again, the story that you need to remember about them is they just they weren't just acquaintances. They were really good friends and they were so normal that they were professors in their mid-

40s who were in between curriculum committee meetings and prepping for classes that just had this shared love of what started with Norse mythology. And they were desperate to write the kinds of things that they longed to read. And it is like looking back, they did not know that they were the CS Lewis and the JR Tolkien. They were just these two friends who were sharing a cider at the pub and saying like, I think we could do a good job at writing fantasy for adults. And so, like to me, just the story of their community, how much they cared for one another and encouraged one another is really what began the storytelling for me. And then the book became an actual shorthand description of where myths and fairy tales come from. So the goals of the book sort of, like all projects, there's a bit of a project creep that happens in every book. This began to creep into a much more meta text using Lewis and Tolkien as kind of avatars to frame the question, where do myths come from and why do they matter?

Valerie -That's an amazing question. I know we've talked about it a lot here on the Bookworthy podcast because you know, Christian fantasy is a place that is growing in bookstores and I think it sometimes does get a bad rap that you know, fantasy is magic, and things we should avoid and but there is a beauty in myth that CS Lewis and Tolkien both grasp and given us these amazing stories that if you're not a Christian, you can read it love it and enjoy it. But if you are a Christian, you can find those little hidden nuggets that we all love. And I think there is a definite power in myth and fantasy and how that can just show us the truth so vividly.

John -Yeah. Well, it's easy to forget that it was not always like this. There were not always fantasy books that were not just for children. The thing that Tolkien and Lewis were criticized for, Tolkien especially, was not that he was making fairy tales that had some sort of spiritual component to them, but just that adults should not be wasting their time with things that are meant for children. And so the predominant point of view on fairy tales and fairy stories at the end of the 1800s and the 19th century was that these were sort of tales for children or for minds that were not yet mature. And so the fact that Oxford professors would invest not just time reading them, but actually, trying to make them was seen as just kind of a colossal waste of their talents. So again, it's very funny to now get to this part of like the timeline and think, oh, no, this is now this extremely credible genre that that all the offshoots in fantasy and storytelling for adults today, even in television and movies, they all can be traced back to Tolkien and Lewis in a lot of.

Valerie -Very true. And I love the friendship between Tolkien and C .S. Lewis that, you know, they didn't agree on everything, but they had a mutual respect and love for each other. And I love the idea that some of the narrative and the back matter that you've put into this book is talking about that friendship and what makes a friend. Because, you know, I think there is this misconception as a parent that, you know, friends have to be just like you and they have to agree with everything you say. I love that CS Lewis and Tolkien have mutual respect and love for one another, but they didn't always agree. How did you incorporate that into your book?

John -Well, it's yes, they shared a lot, but they were also very different. So in many ways, it's a story of what a shared fixed point in the universe can do for a friendship. I mean, they came from different parts of England that, you know, Lewis grew up in Ireland in the Protestant world. Tolkien grew up in England as a Catholic, and Lewis lost his faith early on after World War One. And so when they meet, They're almost as opposite as you could be as two people in England, right? One Catholic, one an atheist Protestant. And their sensibilities about the world were very different in terms of the way they taught and thought about literature. They actually diverged a lot even in their shared interest. But they did have this thing that was a love for the effect of the story on their heart. They found that commonality even before Lewis became a Christian in the Norse mythologies and the joy that came from storytelling and the kind of mystery of where that joy comes from. Lewis called it longing for northernness. Later in his

writings, he described this feeling as the German word, Zennzucht, which means a longing for longing. Or like he would later say, it's like the smell of a flower we've never seen before, right? Like how do you have this longing for something that you could never fully identify? And they both shared that and they were both kind of on a quest to figure out where that came from.

Valerie -That's very neat. It's one of those, like you had said earlier, that started fantasy as we know it today. And they just brought in so many great elements of Norse mythology and Irish folklore and all kinds of myths and... just to pull in and to draw us in to just a great story. What have you seen in this as your research, this story, just what, I guess the, what's the word I'm looking for? I know you kind of talked to it as the, you know, the idea of relying on the myth or the storytelling device. How have you used that in your book?

John - Oh yeah, well, I mean, anytime you're trying to tell a story, whether or not, most of my books are nonfiction, right? They are trying to tell the reader something true about the world. I'm a translator. I'm not a scholar. I mean, I make these things as a work of art. So I'm reading secondary sources. I'm not going to original manuscripts and finding new scholarships. I take the existing scholarship. And then I translate it for my audience. And so my audience is young people. And so every time I do that in any book, I have to take some things out. Like it's the hardest thing is editing. It's not what you put in. It's what you leave out. So with Lewis and Tolkien's story, there is just so much there's so much you could talk about. So like I am not an expert in actual Tolkien lore. Like I have, of course, read the Simmerling a couple of times. I've read all the I mean, I've read much of his work. I spent more time instead of in this book, poring over the deep mythology of, you know, first-age Middle Earth. I spent more time

reading Tolkien's letters, right, because I wanted to understand their relationship and their friendship is so fascinating, partially because, of course, it produced this like hothouse that made this furnace of creative works that just flew out of their fellowship around the Inklings. And then, of course, it burnt out, or it flew a little too close to the sun, or whatever metaphor you want to use. And they had a falling out at the end of their life. And so there's a tragedy wrapped inside of this model of friendship. So it's like, just as a story, it's compelling. It's almost more. I mean, a lot of people feel a lot of sadness about that, that they had a falling out. And in some ways, like that tells the real story of life on Earth. Like it's it's just it's it's tragic. It's sad. I tried in the book to give some closure to that in a way that that I took some creative license. I won't spoil it for the readers, but I tried to give some closure to that. But as just a pure piece of the story, in some ways, it's more interesting that their friendship ran this full arc of the human experience, as opposed to being just the same thing their whole lives.

Valerie -And I think that's why we're so drawn to, you know, this relationship between these two men is that you know, we are given this idea of what friendship is supposed to look like. And while they did have mutual respect and they did have a love for one another, you know, just that fact that they did in their relationship and their friendship, you know, it's like, oh, wow, this is just like my friendship with so and so that I, you know, the argument I had the other day and it really shows a side of friendship that's hard, that we don't like to talk about and that there is a way to walk through it well. I mean, I don't know exactly how their friendship ended, but it seems to have ended to where they still have a mutual respect for one another.

John -Oh, yeah. I mean, that's the tragedy of it in some ways, is they were British men. They were not comfortable with their feelings. They did not know how to center the things that they felt in their life with one another. And when Lewis got married to Joy Davidman, that was the fulcrum that just cracked the foundation enough. I mean, Tolkien famously did not like the Narnia stories. He became increasingly uncomfortable with all of Lewis's theological writings. I mean, to be fair, Tolkien didn't like anything. I mean, he just had very particular tastes. He didn't even like his work. Right. So like we can't use him as the barometer for what he liked or didn't like. But like, again, just as a portrait of two men growing older, meeting the sort of stresses that come with later life. And seeing how that impacted their friendship. And I mean, you read the letters from Tolkien after Lewis died. He was he was crushed by by losing Lewis basically without warning. And I do think he ended up regretting a lot of what they missed in those final years together. Now, they were they were cordial at the end of their life. They would get beers together in the company of their friends. And but the the real the real Jonathan and David closeness that they had in their 30s and 40s was never there after Lewis married Joy.

Valerie -Yeah, it's one of those, we all have that one friend in our life where we've, something has happened where it is a location change sometimes, or sometimes a change in family status or opinions that change us and I think that draws us to these characters that have shaped literature so much. Now you have your little group of inklings that you participate in called the Rabbit Room. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

John -I'm a real fan of community and I think it's why I teach. I think our work almost always gets better in the community. So even as artists, we tend to think we're these islands or we just make things on our own or we're selfish. We spend all this time alone. But the community is essential just to be a human being, let alone the command that Jesus gives us to be in community with Christian brothers and sisters. So like, whether or not you're on the Christian side or the just anthropological side, we need we need people. And so, yes, like I have I have been blessed to present and to be part of the Rabbit Room community and also Hutch mood over the years, the Rabbit Room annual conference. I did Hutch Mood in England in 2019 when I was doing research for this book which was held in Oxford and just have great memories of being there with friends who have a shared love of fairy and story and the Inklings. And so it was almost like being in a kind of Disney World, an Inklings Disney World for a week.

Valerie -So fun. I know. What is it? I've heard that in Oxford, wherever his CS Lewis's office was, there was a lion on one side and a fawn on the other, like a statuette outside of his door. Is that true?

John -There is a, well, you can't get up to his quarters at Maudelein College, but there is a passage in Oxford just down the street from Maudelein. And there's funny, all these inkling-like tours you can take along Oxford. And there is a notable door with a lion on it. And then right across from it is a lamp post that feels, you know, very, very reminiscent of a famous lamp post. So, you know, Were these inspirations? Who knows? But it does seem kind of cool.

Valerie -It's very neat. It's, what is it? I got to visit Oxford as a teenager once and I guess my love of CS Lewis hadn't grown to the place that it is now. I think my experience in visiting Oxford now would be totally different than when I was 16.

John - Yeah. Well, the Eagle and Child, their famous pub, was open when I was there in 2019 and it was closed a few years ago. I believe to be it was bought and renovated. So I am not sure. I believe it is opening soon. But the other one they went to, Lamb and Flag, right across the road. It was closed as well, but now has reopened. So.. I think when you go to Oxford now you can go to at least one of their two favorite haunts.

Valerie -Very fun. I will have to put that on my bucket list for sure. Now as an artist, it's often kind of, or at least the artistic world is often seen as a non-Christian space. What encouraged you to move into, and use your art in a faith-based way?

John -Yeah, I think overall, I think it does not behoove us as faithful people to think of the world as a kind of sacred, secular game of Tetris, right? Where we have to figure out the safe Christian spaces and the not safe secular spaces. We were Jesus told us that the weeds and the wheat will grow up together. And so I encourage you to move out into the world and make the things you are most interested in making. And you don't need to parse out where that goes in the world if you're just faithful to your calling. And I think you're faithful to your calling by the things that you are interested in, whether or not that's a robot or a plant biology or, you know, fawns carrying packages under lamps. These are things that Lewis was faithful to his vision. He did. He had seen images in his head of the Narnia books. And he said, at one point, I don't have any idea why at this particular time in my life I decided to write a book for children. But he listened to that desire, whatever it was. And looking back, maybe you say that's the Holy Spirit. Right. But I think for me, I was going out of art school wanting to be an illustrator. I didn't have a longing to like be a Christian illustrator. Honestly, I think I would be

stunned if you told the 23-year-old version of me that now I make books that are, well, some of them have literal Jesus in them. Like, I think that would stun me. And I think part of it was at the age I was coming out of art school, there just wasn't a lot of Christian art that I liked or art that tried these themes on that was interesting. And so in some ways, I wanted to make the best stuff I could. And that almost excluded making work that was faith, faith-oriented. So now we're so blessed with many artists who are doing things in the world, making artistic interpretations of the gospel story that are unusual, really interesting. And to me, that's the biggest bummer about people who make art for God is that usually, it's just not very interesting. Go and make the most interesting, the weirdest possible thing you can, and see who responds. See who your audience is in the world. It's cultivating an audience out in the world.

Valerie - Very neat, I love that. It's kind of one of those, you know, art itself is not meant to be one thing or another. It's meant to draw emotion, to make us think, to make us explore. And I love your art is so detailed and so woven in and unique that, I mean, my kids will sit there and just stare at a page. They may not be reading the words, but they're just inspecting the drawing because there are so many different levels and so many little hidden things that you have in there. And it just makes art interesting. So now not just your art interesting, but history interesting.

John -Well, I and I make that art that way because that's the book I wanted to read as a kid. I loved Where's Waldo? I loved books that I could pour over many, many times, the Jan Brett books or Graham Bass or any of these books that just felt like they were so full of visual wonder. Right. So in many ways, I make those Easter eggs for myself as much as for the kids that are reading the books.

Valerie -Well, I think that's great with our kids in this social media, very visual-heavy world where just their brains are not geared towards sitting down and reading a 300-page book as much as they were 20 years ago, but they engage with visual stimuli. They engage with, you know, art and graphic novels and those types of things that really pull them in, and along the way they are learning and grasping truths and information that they may not have explored if it was in just a novel format. So I really appreciate what you're doing.

John -Yeah. Yeah, I mean, Faithful Spy, I've heard many people say it can be a kind of gateway book for reluctant readers because there are so many images, and there's so much variety. It doesn't feel that thing. I remember it as a kid. I was a bad reader as a kid. I was so intimidated by pages and pages of text that even my earliest memories reading The Hobbit were like, I couldn't wait to make it to the illustrations I would flip through to see when the next picture was coming because it felt like Rivendell. It felt like a break in between on this long slog of a journey. So like, yes, Faithful Spy was written again for me. I wish I could learn with images interwoven with text whereas a book is like 100 % words and 100 % images at the same time.

Valerie -I know one of my kids is dyslexic and so your style of books has really engaged him in a way that he may never have learned about, you know, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and, yes. Right.

John - Oh yeah, one kid is going to pick up a biography on Dietrich Bonhoeffer at age 12. So to me, I find that a high compliment that any 12-year-old would read a book about a German theologian.

Valerie -Yeah, it's very neat. Now when did you first become interested in art?

John -Oh, I mean, I don't remember the first I don't know. I don't remember the first drawing I ever made. I've been drawing for as long as I can remember. And I've been the other thing I tell people is like, I don't remember the first time I heard about God or Jesus. So like on some level, much of my life has been I grew up with pictures and being inside the church and drawing in church all at the same time. So I've been drawing for as long as I can remember. Most of it started with copying Garfield comics or comics from the newspaper. I love the far side. I love Garfield and peanuts. And I mean, that's that's where drawing started to me. It was just an extension of who I was. Yeah.

Valerie -Amazing. How would you encourage parents who have children who are creative and show an interest in art? How would you encourage parents since we have some parents listening?

John -Yeah, it's funny. I mean, I think I get a lot of emails like my kids are creative. Do you do drawing lessons or do you know anyone that does drawing lessons? And I think most parents imagine lessons are the right format for this because they probably like music lessons, right? But that's not how drawing works, right? It's just it's a different thing. The best thing you can do if your kid is creative is to have lots of supplies on hand. You know, like have a station where the kids know they can go and draw, and on the back wall of that is paper and markers and you don't clean it up afterward. It's just left out and it's a station where they can go and sit down and immediately start making. There doesn't need to be any planning, any prep, any... Because starting is always the hardest part of making. And if you can just make drawing a part of your daily life, your daily practice, something that you honestly can't get out of the way of doing, that's how you learn. You learn almost in all art forms. You learn by doing it more than learning about doing it. So you just have to be in the way of making drawings almost every day and you can and you can start to grow.

Valerie -I love that. Cause what is it? I think Macaroni Grill is a restaurant that usually has white butcher paper on the table. Instead of eating my food, I'm usually there just drawing randomly and it just engaging.

John -Great. Honestly, you should, I mean, maybe it's like putting butcher paper all over every table you own. Like maybe that's a really good practice.

Valerie -I know, I kind of consider I have some creative kids and I'm like, you know what? I might need to go out and get me some art paper. I know my 15-year-old who was excited about this interview would give me the stink eye if I didn't ask this question, but how would you encourage a kid or teen in my case who wants to tell stories with his art?

John -Mm-hmm. Yeah. Well, I think the way you learn is to do it. So what you can do with your kid is encourage them to not just make stories, but actually like make a little zine, make a little book, make something that is a finished product that has a kind of like destination and a place to live. We all need deadlines and a destination or an audience for our work. So, whether it's like make a shelf on your bookshelf somewhere in the house that's like these are my kids' story shelf and we're going to publish their book and it goes on that shelf. And a zine is just another way to say like a bunch of Xerox copies that you stapled together and folded in half.

Right. But make the habit of making little things together and sharing them. Make multiple copies. Have people read it? That's how you get better at storytelling: to practice it and to do it. There's no there's no like there's truly no formula. There's no technique. There's nothing other than you've got to practice. And to practice, you have to enjoy it. And to enjoy it, you have to want to do it. And so if you could do those three things, it's like seems so simple. But that is how you get better. It takes so long to become a good artist or a writer. And the way you get through all those hours of practice and failing and not doing exactly what you wanted to is to enjoy it.

Valerie- I, I do watercolor is kind of my current art niche. And I have included part of my quiet time with God is kind of, you know, I read a passage, I paint something and it's been interesting to watch my kids be like mom, that doesn't look right. It's like, yeah, I messed up. This didn't turn out well. It's like, well, are you going to tear the page out of the book? I'm like, no, it's part of this whole journey. It's part of learning how to use this medium and it's been interesting to watch them be like, it doesn't have to be perfect. I'm like, no, it doesn't have to be perfect. Art doesn't have to be perfect. I just have to try and express myself to communicate something. Sometimes it's just to me like I need to wait a lot longer because watercolor takes patience, apparently, but it's really interesting to see them watch me do my art and just have them think, you know, those perfectionist lines that keep, you know, are drawn often as you look at masters of, you know, and in their schools and such. It's like, well, yeah, Vango and Monet, they didn't get it right the first time. They made thousands. And so it's just, it's fun to watch kids understand or grasp art a little differently because it does have a...pedestal that it's on often. Well, John, what can we expect next from you?

John -Well, I am pleased to announce, as we talked about earlier, that my book, The Mythmakers, will be out this September. This book has not landed yet, but you can see what it's going to look and feel like. Wow. Very exciting. Oh, here, look, I got a proof of the case cover. You won't hear this on the podcast, but the foil stamp. Oh, very nice. I know. Truly the best part of making books is the little last finishing details, but that'll be out this September. And then the book I currently have on my desk I'm working on is a follow-up to my book,

Drawing is Magic, which will have been out 10 years in 2025. That's right. There it is. So I'm doing a follow-up to that to kind of celebrate the 10th anniversary of Drawing is Magic and to

give students and young artists some new ways to think about drawing in a sketchbook. It'll be called 100 Things and it'll be focused just on the 100 Things exercise from that.

Valerie - I will be looking for that for sure because I know drawing this magic has been a big fun thing in our household for sure. Where can people find out more about you and your books, John?

John -Well, you can go to www.JohnHendrix.com. That's Hendricks with an X like Jimmy.

Valerie - Well, thank you so much for being with us today, John.

John -Thanks, glad to be here.

Valerie - Wonderful and thank you for joining us on the Bookworthy Podcast. We look forward to hearing more from John and more about his books here soon let us know in the comments whether you would choose The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, or The Hobbit as your favorite book. And be sure to like and subscribe so we can discover more great books together.

Happy reading!

Comments